Some weeks ago in the pub, I was introduced to some anarchist friends-of-a-friend, who were hell-bent on the overthrow of global capitalism. I thought this was sad, as it seems to me that global capitalism is a jolly good thing. In any case it's never nice to trample on the ambitions of others and so we had an interesting discussion about quite how global capitalism might be overthrown. I would say `watch this space', but as I say it's not me who's interested in overthrowing capitalism, so this would be quite the wrong `space' to watch; and anyway I think capitalism's got a good few years left in it yet.

Another, not entirely unrelated, topic which came up was the question of electoral systems. Tom Steinberg also dropped a similar question into an email a little whole ago, so I thought I'd recycle my thoughts from the pub. (Thus turning the purpose of this web log -- usually characterised as `giving my friends early warning of what I'm likely to bore them with in the pub' -- on its head. Whatever.) Arguably most of the following is obvious, but that's never stopped me before. (At this point I'm also going to say the words `Arrow's theorem', in order to stop anybody from sending me email complaining that I'd left them out. I don't discuss Arrow below, though.)

Presently MPs are elected by geographical regions. This has advantages (each constituent has an identifiable MP, who lives locally and can easily be contacted by the local citizenry; this was more important before the railway, telephone and so forth were invented), and disadvantages (chiefly, that MPs are likely to have parochial interests; this leads to `pork-barrel' politics, especially, for some reason, in the United States). Another problem with geographical constituencies is that they are vulnerable to gerrymandering, especially when the relevant boundary-setting authority is under political influence (as in parts of the USA -- see Economist articles passim).

As a thought-experiment, consider an alternative way to partition the country into constituencies. Instead of dividing it up geographically, we will divide the population into equally-sized groups, at random. We allow the members of each group to communicate with one another via a mailing list or interactive TV or whatever, and come the general election they vote and return a single MP. (The point here is that lots of people don't know their neighbours any more, so why should they be expected to vote with them?)

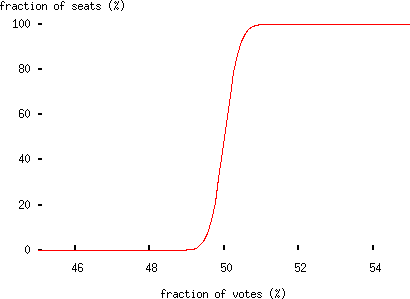

It turns out that this is a staggeringly bad electoral system, because each constituency is statistically identical. Just as an opinion poll sample of 1,000 people almost always yields more Labour than Conservative voters (at the moment), these random constituencies would turn overwhelmingly to whichever party had the greater support. Considering constituencies of 50,000 voters and a two-party election, the results will look like this:

| support for party in population | fraction of seats won by party |

|---|---|

| 50.0% | 50.0% |

| 50.1% | 62.4% |

| 50.2% | 73.6% |

| 50.3% | 82.9% |

| 51.0% | 100.0% |

-- not much good, unless you're one of the 51.0% of people, and even then you might balk at an outcome which would have shamed Saddam Hussein. (For the interested reader, the reason for this is that the probability that more than a given number of the voters will choose one party in any given random sample is given by a Poisson distribution. With a large number, N, of voters each with probability p of voting for party A, this looks like a normal distribution with standard deviation sqrt(pN) -- this is a very narrowly-peaked distribution. In this case it means that the electoral system collapses the whole dynamic range of its output onto the middle ~0.6% of its input. Since I'm rapidly gaining a reputation for filling my articles with supporting pictures, here's one to pad things out:

-- not promising.)

So random constituencies do not make for a representative electoral system. What if we allow people to choose their constituency ahead of time?

(The question which inspired this was, `why do we have MPs who represent geographical regions, rather than issues?' The answer to that is historical, rather than theoretical, but this thought experiment was supposed to be some kind of answer to how you might go about doing that.)

Let's maintain the condition that constituencies are equally sized and fixed in number. We need a fair algorithm for filling the constituencies with voters. So, we propose a random first-come, first-served procedure, in which each member of the electorate is asked in sequence which constituency they would like to join (by number perhaps). If that constituency is full, they are asked to choose again, until they have selected a constituency.

How does this behave?

It turns out that this isn't any good either. Suppose that you are a supporter of a minority party. Your aim is to win as many seats in Parliament as possible, which means putting 25,001 of your fellows in as many constituencies as possible. You agree to fill constituency no. 1 first, then 2, and so forth.

Your opponents (again imagine a two-party election) would like to minimise the number of seats you win. To do this, all they need do is put their voters into the same constituencies you've chosen; since there are more of them than there are of you, they can systematically outvote you in every constituency you contest, leaving them unchallenged in every other constituency. (This assumes that communication between a party and its members is public; this seems likely in practice. If it isn't, then this system degrades to the equally bad random-constituencies one.)

Right. Enough of this digression into bonkers electoral systems. What (if anything) have we learned?

The thought-experiments lead (circuitously) to the following observation: our current electoral system only works at all because political opinion is geographically clustered. If you remove the geographical element, you'll also have use something that's not first-past-the-post, unless you're prepared to put up with incredibly extreme election results.

Why do geographical constituencies work, then? My guess is that it's to do with the localisation of industry (in the broad sense). An urban constituency which contains a car plant will vote for protectionism; an urban constituency which contains a port will vote for free trade. A rural constituency consisting of sheep farms will vote for subsidies; one that consists of market gardens will vote against. Aldershot will vote for war, and Islington for peace (well, prior to New Labour, anyway). And so forth.

As industries becomes less geographically localised -- probably inevitable with the decline of manufacturing -- our geographical system will work less and less well. We can see this already in rural areas which are turning Labour as a result of migration from the cities. Farmers traditionally vote Tory because they were `in favour of the things everybody else is against': fox hunting, agricultural subsidies, conservative social policy, and so forth. Now, farming is dying and rural yuppies take their urban political views with them, and that increasingly means votes for Labour.

Going out on a limb, does this mean we should expect to see Conservative support for proportional representation some time this century?