A long time ago, Winston Churchill is said to have said that `the best argument against democracy is a five-minute conversation with the average voter'. Similarly, one of the best arguments against a free press may be to read the work of Melanie Phillips, who lately dressed up an attack upon playwright Sir David Hare with some statistics which she supposes discredit his recent play about railway privatisation, The Permanent Way.

The Times reports that,

Adrian Lyons, director general of the Railway Forum, an industry lobby group, wrote to Sir David before opening night asking him to correct the plays central message that privatisation had made the railways dangerous. Mr Lyons pointed out that the rate of train crashes had halved since BR was broken up and sold off in 1994--96. While the privatised industry had suffered a series of high-profile crashes at Southall, Ladbroke Grove, Hatfield and Potters Bar, none had resulted in as many casualties as the disaster at Clapham in 1988, in which 35 people had died.

and Phillips, displaying the same willingness to bend the truth that had me chortling all the way through her recent piece of twaddle about global warming, claimed that this showed that,

Since the driving point of the play appears to be that privatisation was responsible for rail accidents and deaths, this would appear to be a pretty damning blow to Hare's credibility.

Well, maybe, maybe not. Like me, Melanie Phillips hasn't seen the play, but let's assume that her precis is accurate. What about those rail accidents then?

Mr. Lyons makes two claims: that the rate of train crashes has halved since privatisation; and that no crash as bad as the Clapham one has happened since privatisation either. Both of these statements are very carefully chosen. Each, as it stands, is true. The number of train crashes (or, as the HSE describes them, `significant train incidents') has been falling since privatisation (as can been seen from the HSE's annual report on railway safety; the relevant plot is on page 30), from 0.47 per million train miles to 0.20 per million train miles last year. And there has, happily, been no accident as ghastly as the 1988 Clapham accident since then.

But this information isn't really relevant. I -- and, I suspect, the rest of the travelling public -- probably don't care whether they are involved in a `significant train incident' unless they are killed or seriously injured; and they probably don't much care how many others are killed or injured when they are involved in a crash. A more sensible approach is to look at the total number of deaths in rail accidents.

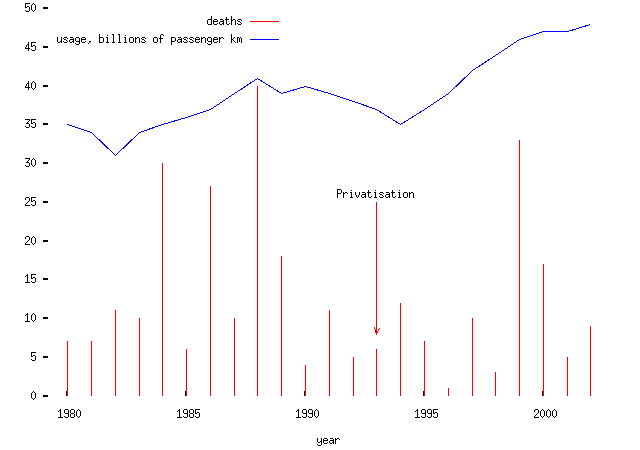

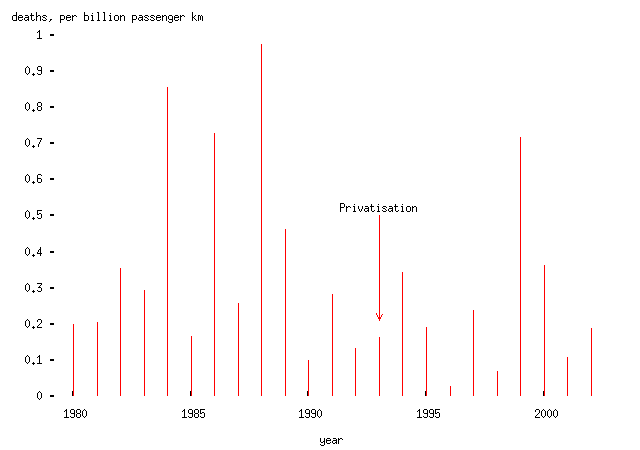

Data on this come from the HSE and from the NSO's splendid publication, Social Trends:

As ever, it is hard to draw any very useful conclusions simply by looking at the plots. Testing the hypothesis that either deaths per year or deaths per passenger kilometer have been falling yields the following:

| Variable | Mean pre-1993 | Mean post-1993 | t-statistic | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| deaths per year | 14.3 | 10.3 | 0.941 | 0.821 |

| deaths per billion passenger km | 0.386 | 0.240 | 1.435 | 0.917 |

That is:

- There is no statistically significant change in the absolute numbers of deaths per year since privatisation.

- There is a marginally statistically significant (10% level) change in the numbers of deaths per billion passenger km since privatisation.

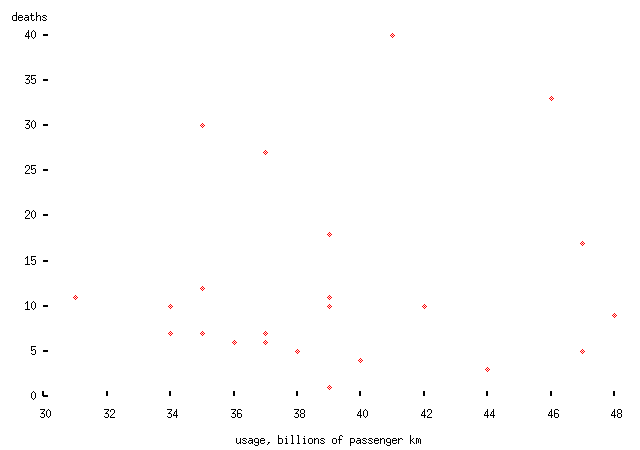

The problem with the latter -- beyond the rather weak significance of the result -- is that there doesn't seem to be a very strong correlation between deaths and usage anyway, so analysing death rates on this basis is bogus: (R-squared is about 0.1.)

Now, as with road accidents, we suffer from the fact that rail accidents are generated by a very random process (it doesn't seem to be Poisson, as it happens) and so a naive analysis like this probably won't get us that much further.

But I would be very cautious to report that we yet know anything about the long-term aggregate effects of privatisation upon railway safety. Anecdotal and expert evidence about shoddy maintenance should give us more pause than these statistics, or those facts which Adrian Lyons so carefully chose to make his case.

At this point I should say something about the notion that `facts' about railway safety -- even if they were true -- can be used to `discredit' a work of drama about railway privatisation. (I'm obviously handicapped here by not having seen it yet and therefore can speak only very generally.)

I'm very unhappy with this idea. A play is, after all, a work of fiction (even if based in accounts of real events). Should the play be pulled from the stage if it is somehow discovered that privatisation has made the railways safer? Of course not, any more than an absence of evidence for effective witchcraft in eleventh-century Scotland should stop productions of Macbeth.

The playwright's job, in the end, is to entertain the public; the journalist's job is also to entertain, but starting from the facts. I have no evidence that David Hare has failed in this duty -- whereas Melanie Phillips certainly has.