30 June, 2003: Disproportionate

Recently I wrote to my representatives in the European Parliament about software patents. (My message was, `vote for software patents and you lose my vote'.)

MEPs used to be elected by the first-past-the-post system used for Westminster MPs, but with much bigger constituencies. (There are 87 UK MEPs, one for every 675,000 people, compared to 659 MPs, one for every 90,000.) Now they are elected using single-transferable-vote on a party list.

This means that in each `region' of the UK, there are a number of MEPs, who collectively represent the region's citizens. In the Eastern Region (East Anglia plus a bit), there are eight. If you want your representatives to know your views, you have to do a mail-merge and post eight letters. (In the South East region, there are eleven MEPs.)

So at the most basic level, lobbying the European Parliament costs much more than lobbying the Westminster Parliament. This may seem trivial -- a stamp only costs 28p -- but inconvenience is important. I'd never thought about this effect when pondering electoral systems. Here's a different take on it, from the 1998 Report of the Independent Commission on the Voting System, discussing the Republic of Ireland:

101. It was also suggested that the constituent with a grievance does not so much go to the TD [Teachta Dála, member of parliament] of his choice as go in turn to all three or four or five of them, according to the size of the constituency in which he or she lives, thereby wasting a good deal of the time of ministers, civil servants, TDs, and indeed of the constituents themselves.

-- note the order in which the various people are listed.

But a grievance is different from an opinion. If I have a grievance, probably a single MEP could address it -- or, if not, try to persuade their colleagues to assist. But if I want to influence the outcome of a vote, I'd be foolish to contact only one MEP, since (a) my opponents are probably less scrupulous; (b) there's no sensible way to choose just one.

29 June, 2003: Another miscellany

I've been away for a while and haven't written anything here. So here are a few `memes and schemes' which have come up in conversation:

Penguin mating rituals

This came up in the pub, roughly like this:

It's difficult to distinguish male from female penguins. Even penguins find this hard. So, when a male penguin wishes to find a mate, he obtains a pebble like a penguin egg, and gives it to a candidate female penguin, to see whether `she' steps forward to keep it warm. If she doesn't, then she's probably a he (or not interested) and our hero looks for another target.

Supposedly this was investigated by a zoologist who hung around a penguin colony photographing penguins and making notes. Towards the end of the day he noticed that he was standing in an enormous pile of pebbles....

This is partly true. Only Adelie penguins -- named for the wife of explorer Dumont d'Urville -- do this, and it's only partly so that the male can figure out the gender of his intended.

There's a useful account at the -- frankly, weird -- Museum of Conceptual Art:

Next, offer your prospective female a well-chosen pebble, preferably a shiny, multi-faceted one costing a wing and a flipper. If she accepts this as a token of your affection, the match is on. (If not, you may have picked an unready female or even another male, a common mistake.)

Actual biologists write in a more sober fashion:

The giving of pebbles to the female by the male is part of the nesting courtship.

And Hollywood will turn anything into a motion picture, The Pebble and the Penguin -- not one of its finest:

Plot summary: A lovable but introverted penguin named Hubie plans to present his betrothal pebble to the bird of his dreams.

User comments: Would it surprise you that my ears and eyes almost bled from watching and listening to this awful movie? ....

No news on the researcher finding himself ankle-deep in gravel, though.

Jaffa Cakes

Another (sub)urban legend: Jaffa Cakes are cakes, as the name suggests and contrary to the claims of HM Customs and Excise, who argued that they were biscuits. This was not an exercise in pedantry but an attempt to levy VAT on them: cakes are `food' and zero rated, while biscuits are `luxury items', and attract 17.5% tax. (Note that the McVities Jaffa Cake web site calls them `biscuits' anyway....)

The matter was settled with this test: a cake starts off soft and goes hard when it is stale, but a biscuit starts off hard and goes soft when stale. Jaffa Cakes harden when stale.

I can't find a proper report of the case, but it's consistently described on the web and I'm happy that the above is right. For instance, from reader correspondence at silicon.com,

The matter was settled over ten years ago by a VAT tribunal in a very expensive case. McVities argued that they were indeed cakes (and hence zero-rated for VAT), while HM Customs and Excise argued that they were biscuits and hence subject to 17.5 per cent VAT. McVities won the case, primarily because biscuits are hard when fresh and soft when stale whereas cakes are soft when fresh and hard when stale; Jaffa Cakes, of course, fall into the latter category. I have a recollection that McVities also baked a cake-sized Jaffa Cake for the tribunal chairman to support their legal arguments. God, I should get out more...

Or, from the South China Morning Post,

Chocolate biscuits are defined as luxury items, so liable to the tax, while cakes are basic foodstuffs and zero-rated. McVities argued that a Jaffa Cake is just that.

The famous case ended up centring on how Jaffa Cakes aged. The firm argued that a biscuit was hard when fresh and soft when stale. Jaffa Cakes, in contrast, went from soft to hard. The company won.

Or, from solicitors Clifton Ingram,

The `when is a cake not a cake?' riddle was solved some years ago and related to Jaffa Cakes. A Jaffa Cake was found to be a cake, not a biscuit, and therefore outside the confectionery exception.

And, irrelevantly... there I was thinking that `Suburban Legends' would make a great name for a band -- and it turns out, it already is! You can listen to their music at MP3.com. If I try to review music, you'll all laugh. (Maybe you do anyway.) So listen to it yourselves. You'll need to `register' to download the MP3s.

Submerged floating tunnels

James was talking about the idea of building a fixed link across a fjord or other waterway using a sealed tube hanging in the water. It turns out that this idea is real, though nobody has actually built one yet.

The game is: build a floating tube, string it across the body of water you wish to cross, then sink it, leaving it suspended underwater. Designs either have positive buoyancy and are anchored to the sea bed, or have negative buoyancy and are hung from floats -- a bit like a suspension bridge. A further suggestion -- not yet feasible -- uses a neutrally buoyant tunnel with no supports or anchors except at the ends. A workshop was held last year in Seattle to discuss the concept; there are some useful diagrams on their web pages, as well as some information on various proposals.

(I don't know how you would choose the support method to use. Presumably hanging it from floats creates a problem with wave loads during storms, but I don't know how serious that is.)

Why on earth would anybody build one? They're cheaper than bored tunnels, and unlike floating pontoon bridges, ships can easily pass them (since the tube can lie far below the surface). But... a brief discussion from a page about building a fixed link to Vancouver Island from the Canadian mainland identifies some problems:

A submerged floating tunnel would also be very expensive. The estimated cost would be two to three times more than a floating bridge. The technology is currently unproven. No submerged floating tunnels exist in the world today.

A submerged floating tunnel to Vancouver Island would require large gravity anchors, which would be complicated given the deep, soft soil on the ocean bed in this area. It would provide better passage for large vessels, but safety is a critical concern. A submerged floating tunnel would be vulnerable to marine accidents and earthquake damage. A tunnel break would be catastrophic and could result in the loss of many lives. For these reasons, the existing technologies for this type of submerged floating tunnel do not make this option feasible at this time.

The Norwegians seem to like these things, with a company called the Norwegian Submerged Floating Tunnel Company AS, involved in designing SFT fjord crossings. Sadly their website is pretty content-free.

There's also a report on structural aspects of SFT design which has a good general description of the idea: (but too few pictures)

Floating submerged tunnels has never been built in full scale, as opposed to surface floating bridges. In Norway the fjord Høgsfjord between Lauvvik and Oanes has been proposed crossed by means of a ca. 1400 meter long submerged tunnel, thus possibly making it the first structure in the world of this kind. Traffic prognosis predict about 2500 vehicles passing the bridge daily, placing it as an important regional transport vein in the south-west coast of Norway.

This Høgsfjord project is deliberately used as a pilot project for skills upgrading on the field, providing ``know how'' on strait crossings with this kind of long slender floating structures. Dealing with global dynamic analysis of floating submerged tunnels, the present report is a part of this picture. As such, it follow research effort on the area from the last couple of decades. Earlier though, the emphasis has often been put on surface floating bridges, in Norway leading to the building of the Salhus bridge (now officially named Nordhordlands-brua) early in this decade. The floating submerged tunnel concept are a quite similar concept concerning the interaction with the surrounding sea, but there are differences to be aware of. Since the concept has not been built before, thorough investigation of loads and effects should be effectuated taking special conditions for the particular Høgsfjord site into account.

The Høgsfjord project has been going for a while, but nothing has yet been built.

An `Orwell Test' for pubs

In 1946, George Orwell wrote an essay for the Evening Standard entitled `The Moon Under Water'. It describes Orwell's ideal pub; but

... the discerning and disillusioned reader will probably have guessed already. There is no such place as the Moon Under Water.

Of course, there are now numerous pubs by that name, all great plastic drinking barns run by J D Wetherspoon. For their sins, they acknowledge his inspiration, ignoring the ghastly hash they've made of it.

(Funnier is this review of the Leicester Square Moon Under Water, by somebody apparently unaware of the Orwell connection, which starts,

Why is it that central London's JD Wetherspoon pubs are infatuated with the moon? Lycanthropy, perhaps? ... There are two Moon Under Waters within puking distance of each other, a Lord Moon of the Mall, and a Moon and Sixpence.

and goes on to say,

... It's a voyeur's dream in this pub, as the disproportionate amount of overt cameras echoes Orwell's 1984....

... Well, I laughed. At this point I should also point out that the plural of Moon Under Water is Moons Under Water, as any fule kno.)

Anyway, returning to the point, since the Wetherspoons `Moons' are travesties of Orwell's ideal, it would be a nice idea to give awards to real pubs which resemble his ideal. His `Moon'

- Has authentically Victorian fixtures and fittings: ``no glass-topped tables or other modern miseries, and... no sham roof-beams, ingle-nooks or plastic panels masquerading as oak.''

- Is spacious, with several bars, an open fire and an upstairs dining room.

-

Is quiet enough for conversation; ``The house possesses neither a radio nor a piano, and even on Christmas Eve... the singing that happens is of a decorous kind.''

(We'd exclude juke boxes, televisions, quiz machines, and sundry other modern inconveniences, too.)

- Is staffed by people who remember the regulars.

- Uses proper mugs for beer, not handleless glasses.

- Has a big garden, with space for kids.

- Is sufficiently out of the way that it isn't frequented by drunkards, but nevertheless is easy to get to -- ``two minutes from a bus stop.''

(I've left out others, mostly anachronistic, and I don't agree with some of the above -- I don't care that much about decor, for instance, and mugs-with-handles are a bit old-fogey.)

So, would it be worth reviewing pubs according to these criteria? I don't know. There are lots of pub review sites, but -- cf. the one I quote above -- their biases may mean that they're useless for actually choosing pubs, so maybe there's a niche here that's worth exploring.

The Still Small Voice Of Reason

A way to enhance news programmes on the radio. The Still Small Voice appears, using the magic of stereo, to one side of the presenters and interviewees, and occasionally mentions important points which have somehow been forgotten in the cut-and-thrust of debate. So,

| When the programme... | The Still Small Voice... |

|---|---|

| says that elderly people who are burgled are at a greater risk of dying than those who have not, | calmly and firmly says, ``selection effect.'' |

| discusses a `polypill' which is supposed to cut heart disease by 80%, | whispers ``risk homeostasis.'' |

| has David Blunkett on, | bangs its head against the table in between screaming, ``shut the fuck up you fascist fuck.'' |

I don't think this would catch on with the BBC, though somebody suggested that a `guerilla broadcaster' could add it to unwilling radio stations using the magic of (a) a big transmitter, and (b) the linearity of Maxwell's equations. Hmm....

23 June, 2003: There are patterns...

Many moons ago I started reading A Pattern Language by Christopher Alexander et al. This is widely regarded as the book which started the present `design patterns' fad, but it is not about `software architecture'. Anyway, with a library deadline looming, I finally finished it....

A Pattern Language -- some sort of review

This is a book about the design and construction of towns and buildings -- what it is now fashionable to call `the built environment'. Alexander et al. proceed from the reasonable ideas that

- particular solutions to particular problems recur in architecture;

- people innately recognise and remember these solutions.

They call a class of problem and its solution a `pattern' and A Pattern Language is a dictionary of these patterns. Each definition identifies a perceived problem, discusses it, and offers solutions (which give the patterns their names). Other related patterns are identified. The dictionary covers artefacts of every scale, from countries to cupboards; the patterns are listed in inverse order of the size of thing to which they apply.

(The dictionary itself would be a perfect application for hypertext, and it is sad that it is not freely available on the web. There is a paid service, though.)

The book was published -- following extensive experimentation by its authors and in conjunction with two other books, The Timeless Way of Building and The Oregon Experiment -- in 1977; its outlook is, perhaps, characteristic of its time. Today, some of the prescriptions Alexander et al. give seem naive or outmoded. For instance, given the general problem that: (pattern 80, `Self-governing workshops and offices')

No one enjoys his work if he is a cog in a machine,

they suggest that employees work only in

... self-governing workshops and offices of 5 to 20 workers. Make each group autonomous -- with respect to organisation, style, relation to other groups, hiring and firing, work schedule. Where the work is complicated and requires larger organisations, several of these work groups can federate and cooperate to produce complex artifacts and services.

An appealing thought, perhaps -- depending on what you think of your current colleagues. I don't know whether this looked more realistic in 1977 than it does today. Likewise, Alexander et al. place tremendous and unfashionable faith in centralised economic planning, as in pattern 19, `Web of Shopping', where they try to solve the problem that

Shops rarely place themselves in those positions which best serve the people's needs, and also guarantee their own stability

-- this is followed by a discussion of Hotelling's problem, which tells us that two businesses competing for custom in the same area will be neighbours, because the first's calculation of the ideal location holds good for the second, too. (This is why you often see McDonald's, Burger King and Kentucky Fried Chicken outlets in a row on the high street.) A Pattern Language argues that it is `better' for the businesses to locate separately, each in its own catchment area, and the suggested solution implies that a planner will decide where shops will go. This idea is a little attractive, but the popularity of supermarkets -- despised by Alexander et al. -- suggests that the attraction is not general.

But the patterns are generally thought-provoking, and disagreeing with a few of the arguments does not invalidate the rest any more than one would reject a dictionary because of a few objections to the definitions presented. The reasoning of Alexander et al. is based upon a variety of sources; often, they refer to psychological studies, but most of the patterns incorporate value judgments based on their own experience. Philip Greenspun writes that

this book has more wisdom about psychology, anthropology, and sociology than any other that I've read

-- and I'd probably agree, with the proviso that I don't often read books about psychology, anthropology or sociology.

The value judgments are refreshing. For instance, pattern 94, `Sleeping in public'--

It is a mark of success in a park, public lobby or a porch when people can come there and fall asleep

-- is unlikely to find much sympathy with today's legislators.

On a more general note, A Pattern Language recommends that builders construct buildings from (pattern 207, `Good materials')

only biodegradable, low energy consuming materials, which are easy to cut and modify on site....

They suggest lightweight concrete, earth, brick and tile; they recommend against any metals, wood as a structural material, and most synthetics. This is accompanied by one of those Limits to Growth type graphs of the time left until we run out of certain metals -- like iron! (About 50 years left, they think....)

Their vision of how to build is very low-tech: they recommend that structures be built entirely in compression, with no more than four storeys, and that they need not -- and, to be `human', should not -- be built exactly to measure from a plan. There's an implicit assumption that everyone should build their own house, which is a romantic if hardly practical idea.

The thesis of A Pattern Language is appealing. Of course, I say this partly because I am sympathetic to many of their prescriptions, particularly those involving urban transport--

It is clear, then, that pedestrians will feel comfortable, powerful, safe and free in their movements when the walks they walk on are both wide enough to keep the people well away from the cars, and high enough for them to drive up on them by accident.

... What is the right height for a raised walk? Our experiments suggest that pedestrians begin to feel secure when they are about 18 inches above the cars....

(As an aside, note that the book employs, in the usual US style, imperial units throughout. It is a truism that these units are more `intuitive' -- by which we mean `easier to relate to'. And I feel this even having had a purely metric education.)

I would like to live in a house designed according to the principles which A Pattern Language recommends, though I would be more wary of living in a country or economy built from the patterns. Of the various buildings I've lived in over the past few years, it's fairly clear that the ones which worked best socially followed its patterns more closely than the modern buildings which Alexander et al. identify as socially dead. Almost all of the patterns suggested for building interiors could usefully be applied to my flat, which is in serious need of a redesign.

I don't know how useful this book is to actual architects. Do they need a book to tell them that there are familiar ways to design bits of buildings? I don't know. But it's made me pay more attention to the world around me.

When, months ago, I started reading this book -- as, essentially, a dictionary, it is not an easy book to read end-to-end -- I was interested in the origins of the `design patterns' idea in programming. Reading A Pattern Language has made me much less interested in the design of software and much more interested in the design of towns and buildings.

As for `design patterns' in software....

It is probably fair to trace to Alexander et al. one of the more irritating habits of the software `design patterns' crowd: the elevation of Pattern (capitalised, emphasised, stripped of article) to the design pantheon. But we obviously cannot blame A Pattern Language for their pretentious Java twaddle or tiresome preaching.

I recommend that you do not read this book to find out about `software engineering'. It is much more interesting than that.

20 June, 2003: Miscellany again

-

-- does this mean that somebody did buy both editions of the same book, or is that not how Amazon works?

-

How horrible that our dear leaders have to be told by the Germans that locking asylum-seekers up in concentration camps is a really offensive idea:

A source close to Gerhard Schroder, the German chancellor, said: ``I think you know what we in Germany think nowadays about putting people in camps.''

-

Re-reading bits of P G Wodehouse, I was struck by how similar the Jeeves and Wooster stories are to Yes, Minister (especially the one short story written from Jeeves's perspective). Grubbing about with Google, I find that Jonathan Lynn has a web page, complete with fascinating factlets --

Q. How and where did you learn the secrets of the civil service...?

A. I think we made them up.

-- and on-line copies of the Gerald Scarfe cartoons from the television programme's title sequence. Better than your average `celebrity' web site.

- Some comments on intellectual-property advocacy which I feel should be taken to heart. (But I would think that.)

18 June, 2003: Get to know your new, uh, neighbours

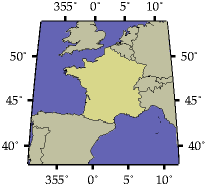

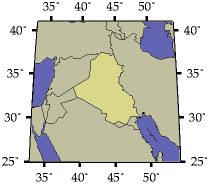

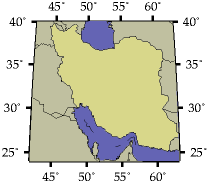

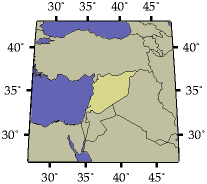

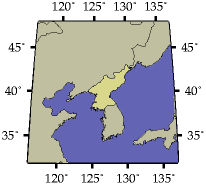

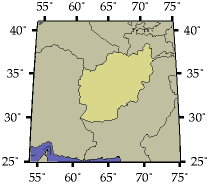

I shouldn't do cartography too often, but I see that various bits of the news media are still reporting that Iraq is `as large as' or `twice the size of' France. This is not the case. For your convenience, here are the comparitive sizes of some countries which are relevant to the new Empire: (maps are in the Mollweide equal-areas projection, and, unlike the CIA's can therefore be used to compare areas directly)

| Country | Area (km²) | Area (Frances) | Map |

|---|---|---|---|

| France | 547,030 | 1.000 |

|

| Iraq | 437,072 | 0.800 |

|

| Iran | 1,648,000 | 3.013 |

|

| Syria | 185,180 | 0.339 |

|

| North Korea | 120,540 | 0.220 |

|

| Afghanistan | 647,500 | 1.184 |

|

(Want to make your own maps? You'll need GMT and some ability with shell scripting. To start with, here is the script used to produce the above.)

Update

Paul points out that the correct journalistic unit of country size is, of course, a `Wales', equal to 20,779km²; Iraq weighs in at 21.03 Waleses. He also raises another interesting question: as we know, the proper journalistic units of length and height are such things as `a double-decker bus' (10m), `the height of Nelson's column' (56m), or `the distance from the Earth to the Moon' (400,000km). But what is the proper journalistic unit of width?

11 June, 2003: No entitlement enlightenment

So, to my surprise, I got a response from the Home Office on the ID cards debate: (as ever, typos mine, mostly)

Entitlement Cards Unit,

Community Policy Directorate,

Home Office.Dear Mr. Lightfoot,

Thank you for your letter to Beverley Hughes. Your letter has been passed to me in the Entitlement Card Unit for reply.

The Government published the consultation paper on Entitlement Cards and Identity Fraud on 3 July 2002. While the formal deadline for submission of comments on the consultation paper was 31 January 2003, we are keen to see the debate continue. We are grateful for the time you have taken to comment on the paper and can confirm that your comments have been recorded and will be taken into account in our analysis of the responses received.

Ministers think it is appropriate to announce the detailed breakdown of responses to Parliament first.

There are strongly held views on all sides of the debate on entitlement or identity cards. We have had a large number of responses to the consultation exercise and are aware that many people will have put a great deal of effort into providing us with their views. We are now in the process of carefully analysing all the responses received.

The Government has made it clear that the introduction of an entitlement card would be a major step and that it would not proceed without considering all the views expressed very carefully.

Yours sincerely,

Carlene Farrell (Miss)

Entitlement Card Unit

This is vaguely promising, but I'm not sure what the third paragraph about announcing the breakdown of responses to Parliament `first' means -- hopefully this doesn't refer to the 28th April statement which set off this whole muddle. I've asked for clarification.

6 June, 2003: Not a rhetorical question

Anne Campbell replied to my letter about the ID cards consultation. She writes,

I have noted your objections to the way in which the entitlement card consultation was conducted.

Note quaint use of the term `entitlement card', and total failure to answer the questions put.

1 June, 2003: If only...

Peacekeepers to solve Cambridge's traffic problems, apparently: